The Startups Team

Welcome to Phase Two of a four-part Splitting Equity Series. If you missed it, start your journey here: Introduction - Early Startup Equity — Getting it Right before continuing on if you haven’t already, and go in order from there.

Phase One - Startup Equity - Avoiding Early Mistakes

Phase Two - Part 1 - How Startup Equity Works

Part 2 - Startup Stock Options

Part 3 - Startup Stock Vesting

Part 4 - Startup Stock Valuation ( ←YOU ARE HERE 😀)

Phase Three - How to Split Equity

Phase Four - Equity Management

Let's continue!

Early-stage startups use a Stock Valuation to determine their fair market value. This will determine everything from how much a venture capital firm might receive for their investment to how we distribute employee stock options.

There are many valuation methods available to Founders, and most understand zero of them! If you're sitting there saying “How would I possibly know what my pre-revenue valuation is?” then you're in the right place!

Popular Startup Valuation Methods

If we're raising capital from angel investors or later on from venture capital firms, we're going to get asked about our valuation. We can probably talk intelligently about revenue growth or even discounted cash flow (maybe) but valuation methods always seem to confuse Founders.

We'll walk through some really simple valuation methods and also touch on a few more complicated versions like the Venture Capital Method. Pick the one that makes the most sense and feels right to you.

The Valuation May Not Matter — Yet

Many business owners get by just fine splitting up their startup companies between just a few co-founders — they don't really need a full startup valuation. We might be contributing some physical assets (like inventory) or intangible assets (like IP) but the average valuation process isn't complicated.

Example

If I contribute $50 and you contribute $150, you own 75% of the stock ($150 is 75% of our combined $200 contribution). Not a bad investment of $150. So we don't need a startup valuation, just a valuation of the contribution we're each going to make.

This is how startup ventures have been divided up since the dawn of time and it works perfectly well. No one is trying to torture a "Market Multiple Approach" or implement the "Berkus Method" we just do simple splits and it works — until later.

When does a Startup Valuation Matter?

During formation, the valuation doesn’t really come into play. It becomes more of an issue the moment we start issuing stock to anyone beyond us. The moment we begin raising capital from an angel investor and need a "Pre-Money Valuation" — that's when we have to dig in for real.

It’ll also come into play if we add other co-Founders later on down the line, although we may still be able to grandfather them into our early math of valuing our equity relative to each other’s contributions.

Why Valuations Matter

It may sound odd that we’re valuing a company so early, especially if it’s just at the idea stage when no tangible product exists. However, a startup's valuation at this stage is absolutely critical to helping us understand how to value the contributions of non-members, such as employees, contractors, or advisors.

A startup valuation puts a dollar value on the business so that people can determine how much the market value of their contribution would earn from the company.

Food for Thought

Imagine that Emperor Palpatine earns $1 million per year as the Galactic Emperor. He meets an aspiring Founder named Anakin Skywalker who has a kickass idea to create a space station the size of a small moon that can destroy other planets.

In this scenario, Anakin wants to hire Palpatine, but needs to know how to value his stock award. If the valuation of that startup is $2 million, then the Emperor can argue that joining the startup should earn him 50% of the company in the first year alone (his $1M market value is half of the $2M valuation).

But if Anakin can convince him the valuation is $10 million, then he would only earn 10% of the startup. That’s a huge delta.

As we begin using our stock as currency, how we set the valuation — and whether others accept it — becomes critical toward providing value to our currency, but also making sure we don’t undervalue and dilute our stock prematurely. More often than not, dilution is what we’re fighting against.

Note that market contributions such as cash or time typically have a fairly well-understood value — we know that if a web designer normally charges $5,000 for a website, then that’s how much we would pay in cash.

So the real variable is how valuable the company is relative to that contribution. Not having a well-established valuation makes the value of a contribution damn hard to ascertain. So let’s try to pin that down a bit.

Startup Valuation Methods

Let’s start by establishing a few fundamentals here. First, there is no magic slide ruler or calculator that we can use to get a Kelly Blue Book Value for our startup, especially in the formative stages.

Many Founders have some foggy idea of what a business valuation looks like when someone calculates a “discounted cash flow” or “20x EBITDA”. They are thinking about the valuations of mature businesses with lots of known quantities. This isn't that.

Instead, we’re going to take a look at pre-revenue valuations starting with the most “data-based” and finishing with the wild-ass-guess methods — all of which are actually used.

Comparables to Similar Startups

If we're in a space where similar companies have a post-money valuation available (Crunchbase.com has these listed) that's ideally the best place to start.

For many in the tech startup space finding comparable companies to our business model that have post revenue valuations or recent acquisitions will be very helpful. Any other business venture outside of tech may still be determined based on public information.

While venture capital investors may have invested at later stages (meaning they were likely worth more) it can at least provide a guideline as to what our startup might be worth. When we look at public companies' expected value we can get a best case comparable but not likely something close to our stage.

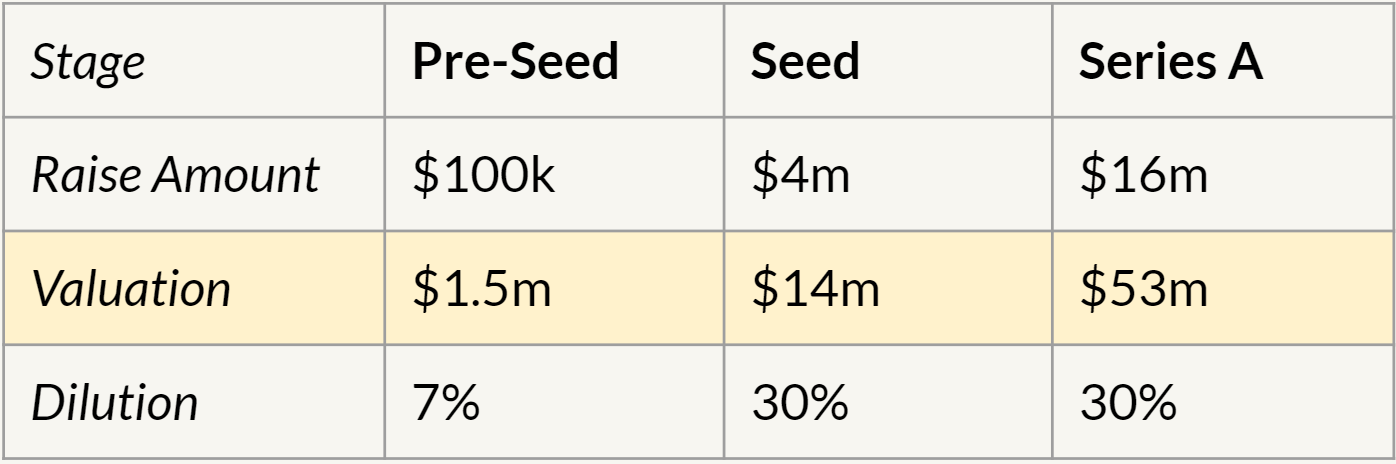

Investment Stage-Based Startup Valuation

Investors tend to calibrate their investment amount toward a specific "stage" of a company's growth. Each stage has a valuation approach that's relative to the total value of the investment round.

For example, many startup accelerators take a 7% stake of a business for $100k in cash invested at the idea stage, presuming a valuation of about $1.5m for idea-stage companies. It’s possible to use comparable methods of how actual cash has gone into similar deals at a similar stage to get a ballpark range for our valuation.

Floating Valuation (Slicing the Pie Method)

A different method of creating a valuation is to “accumulate” the valuation over time by constantly adding up everyone’s contribution and then providing a percentage of that combined total.

If we both invest $100 then the valuation is $200. We both own 50%. If you then invest another $200 and I invest $0, then you’ve contributed $300, I’ve contributed $100, and you own 75% of the pie.

Some startup company founders will use this model when they are accounting for physical assets (like inventory) or other assets that have a clear monetary value. It's also more useful for a startup company that likely won't raise capital in the near future.

Contribution Value

Often a startup company is valued based on the amount of equity a contributor perceives to be valuable. In this case, it’s the tail wagging the dog.

If an investor puts $50k into our startup and believes that a 10% stake is the minimum they would accept (based on very little data) then the valuation of the business is $500,000. We’d be banking on a subjective “feeling” that the contributor has about what a stake is worth. This gets used more often than you’d expect.

Similar to other methods, we value the company based on a single variable ($50k invested) and then imply a full valuation of the startup company from there.

Set a Base Value

Another way to set the valuation is by using a “Base Value.” The idea is that if the startup were to have a potentially lucrative exit, it would have to have gotten to that successful exit with at least "this much value."

For example, if we set the “Base Value” of our startup at $1 million, we’re not saying that it’s absolutely worth $1 million today. We’re saying that $1 million is the minimum that the company could be sold at in order to have any marketable value. Said differently, if the company isn’t worth at least $1 million at some point, the stock is probably worthless anyway.

Use Angel Investor Methods

Angel Investors have been working on far more complex models to determine the valuation of pre-revenue startups. Some of the popular startup valuation methods they have used include the "Risk Value Summation Method" which analyzes a number of elements of risk.

Founders in the startup world rarely use this method themselves when going out to raise capital as this is more of a scorecard method for potential investors and less of a self-discovery method to value a startup's assets.

You can Literally "Make it Up"

Ultimately a startup is worth what the market will pay. If venture capital firms are willing to agree on a speculative valuation of $1 billion of a company — then that's what it is worth in the eyes of the market. This approach is way more common than most founders realize.

For example, if we were raising $1 million in seed stage capital we may set our valuation at $5 million which implies a post-money valuation of $6 million ($1m + $5m). We made that valuation up.

Now when we go to raise, an angel investor may ask "What is your valuation?" to which we will respond "We're raising $1m on a $6m post-money valuation" which informs the investor that they will receive about 17% of the company.

The "make it up" model probably accounts for 80% of startup valuations currently raising.

Awesome. Now We’re More Confused!

We didn’t say this would be easy!

We may look at all of those and say “Wow, that’s great and all, but we still have no idea which valuation method to use!” Ideally, we will move down that list of several startup valuation methods sequentially until we find a methodology that we can agree on the most.

We should first focus on the valuation method we like, then we can determine what number to arrive at.

Let’s say we decided that an “Investment Stage-Based Valuation Method” makes sense to us. We know another startup company in our space that was valued like this, so we can at least agree it’s an outcome we’d like to share with them.

We may then say, “As a starting point, let’s use the same valuation most incubators give to new ideas and set it at $350k.” Remember, if we’re just splitting equity amongst ourselves, the valuation doesn’t matter as much. The amount of equity we get among the Founders will be relative to each other’s contribution. But if we’re giving others equity, this is a safe place to start.

Key Takeaway

First, pick the valuation method that feels the most accurate then use that framework to arrive at a good starting valuation.

Delaying the Decision

If we can’t come to an agreement right now, and it does happen, it is possible for us to punt valuing startups until later. This is actually a fairly common practice amongst startups and investors when negotiating early-stage investments where it's hard to determine a "pre-money valuation" but they believe in the company's future potential.

The thinking goes that neither party can fairly determine the value of the company now, but they really want to do a deal. What they do know is how much the investor is willing to invest.

This type of structure is known as a “Convertible Note” which simply means that the investment amount will “convert to equity” at a later date when a real market valuation can be established — such as the next round of financing with venture capital firms.

The point is that it’s possible to defer this decision for a minute while we make more near-term decisions. But it’s helpful to have the context of what valuation will mean to us as we distribute our hard-earned equity.

Summary

It may not sound like it — but that was the easy part!

Up until now, we haven’t had a lot that we couldn’t agree on because all of the terms affected each member of the company in the same way. Whether we chose to do straight equity or phantom equity — we both get the same benefit.

These decisions put together a very basic framework for how our stock will get set up, but it still doesn’t tell us “who gets what.” That’s where the challenge starts to brew, and what we’ll discuss in the next section.

It’s advisable that before we get into splitting the equity, we try to get some real consensus on all of the formative decisions in this Phase first. This isn’t necessarily sequential, but it does give us more things to agree upon before moving forward. Like any good negotiation, creating some momentum around agreement is key to overcoming the moments where we differ.

And we may be about to differ. Let’s find out.

Find this article helpful?

This is just a small sample! Register to unlock our in-depth courses, hundreds of video courses, and a library of playbooks and articles to grow your startup fast. Let us Let us show you!

Submission confirms agreement to our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.

No comments yet.

Start a Membership to join the discussion.

Already a member? Login