The Startups Team

Welcome to Phase Three of a four-part Splitting Equity Series. If you missed it, start your journey here: Introduction - Early Startup Equity — Getting it Right before continuing on if you haven’t already, and go in order from there.

Phase One - Startup Equity - Avoiding Early Mistakes

Phase Two - How Startup Equity Works

Phase Three - Part 1 - How to Split Equity

Part 2 - Splitting Equity Today

Part 3 - Splitting Equity in the Future ( ←YOU ARE HERE 😀)

Phase Four - Equity Management

Let's continue!

Founder equity splits rarely turn out to be what we hoped they would be after Year 1. The co-founders at startup companies start off with the best intentions, but as the business venture turns into long nights and little income, startup founders start to drop off quickly.

The Co-Founder "Broken Promise"

As a co-founder, I may say that I’m going to work full-time on our startup company for the next 3 years, but until I actually do, we shouldn't split founder equity on the "promise" of a contribution!

Founder equity splits should be designed at the initial stages to account for everything from our struggle in Year 1 to our scale in Year 3 when we're wrestling with venture capitalists. As startups mature, things that might have been split equally initially (like writing that business plan or refining the business model), will rarely continue to be split equally.

We also have to consider that what co-founders contribute to startup firms in Year 1 isn't necessarily the same as they will contribute in Year 2 or Year 3. If we only use a single year to account for the entire growth of the startup company, we may disproportionately reward co-founders who happen to have more value in Year 1 but don’t necessarily continue to pay in that value in subsequent years.

Founder Equity Splits after Year 1

There's an oft-cited study from the Harvard Business School covering why startups fail. What that study falls short on is where the founding teams themselves fail, which is typically after Year 1.

If we begin with equal equity splits with the assumption that whatever happens in Year 1 must be the template for future contributions, we're likely to be sorely disappointed. There are a few absolute truths that many startups ignore:

People Leave

In the early stages of a startup company, it's easy to make big commitments and pretend our financial value will be "forever." But as the business grows and our personal cash flow implodes, co-founders start thinking about how "raising capital" as getting another job! Most co-founders, regardless of how juicy their founder equity might be, simply can't afford to outlast a full year without compensation.

There's a very high risk in setting up an equity split with co-founders that is completely lopsided based on a Year 1 commitment without any follow-through. We love the concept of equal splits but it's very difficult in the early stage of our business to know who is the right partner and who is the wrong partner. Sometimes we are the wrong partner and we don't even realize it!

Relative Value Changes

In Year 1 new businesses often need lots of know-how to get started — legal, marketing, or perhaps finance. We're often still self-funding at this point and venture capital is still a pipe dream. In Year 1 these contributions were critical to getting our business concept launched — but their relative value will likely change we're beyond just business strategy.

Our lawyer or a co-founder with legal skills may be the most important person on the team before we raise money, but offering an equal split to cover costs may make zero sense in Year 2 when we don't have any legal needs. We constantly have to balance what are really short-term needs versus long-term, persistent needs that actually fuel growth.

Individual Contributions Change

In Year 1 I may have invested $50,000 of financial capital as well as my time. But I didn’t invest another $50,000 in Year 2 or Year 3. When we look to raise funds either externally with potential investors or internally through co-founders, we have to recognize that their contributions will likely be a one-time event - not perpetual.

While $50,000 might be all the money in the world to us now, that would likely be a tiny fraction of what we'd raise from an angel investor or some Silicon Valley venture capitalist down the road, so giving up 50% of our Founder equity is likely very premature.

One-Time Contributions Expire

(Warning: this is a big one!) Many of our contributions will be one-time in nature, typically in Year 1 before we're initially funded. Those tend to include things like intellectual property, relationships, office space, cash investments, and other new business-type resources. If we simply project our Year 1 contributions as if they were being made every year thereafter, we’re going to regret it later.

The last thing we want is an entrepreneurship education on how not to give an equity share to someone for what wound up being a single year of value! Although these things sound important to many startup companies right now, they aren't worth giving up the farm for.

The emphasis here is to understand how important it is to split our contribution up over a few years so that we can account for some likely changes that will occur as the business evolves. If you and I both split the business 50/50, we want to make sure that our contributions remain 50/50 on an ongoing basis!

Set a 3-Year Contribution Window

If we know all of these changes will occur, we’ll want to account for these changes deliberately by using a 3-Year Contribution Window. That means we’re going to add up our relative contributions in Years 1, 2, and 3 separately to account for potential changes over time.

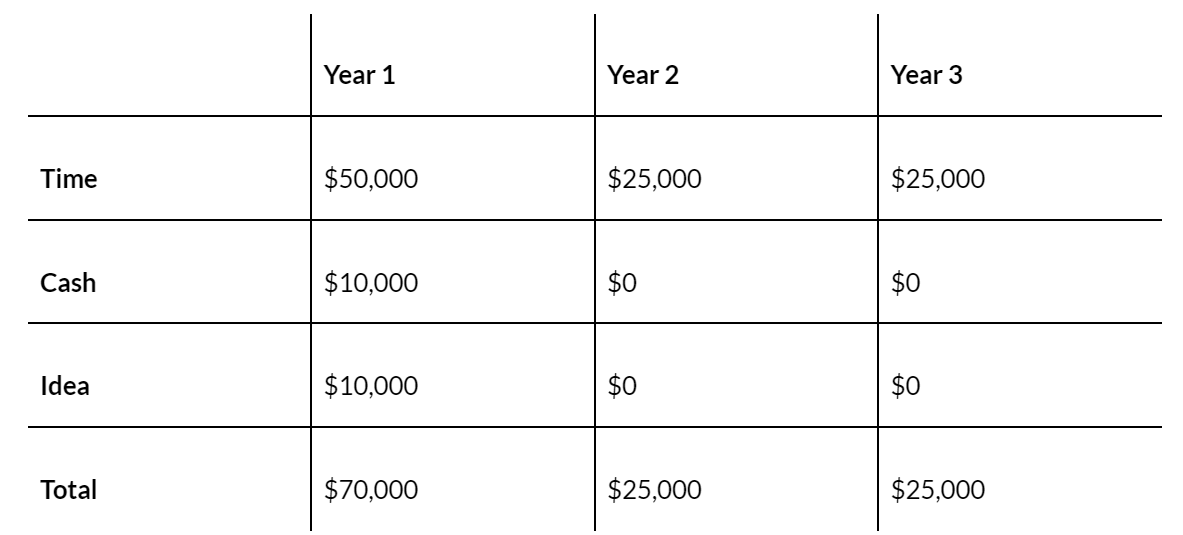

Here’s an example of how my contribution in Year 1 may change relative to Year 2 and 3:

Notice how my commitment in Year 1 is almost 3x higher than my commitment in Years 2 and 3. If we were to value my entire contribution relative to just Year 1, we’d be wildly overcompensating. That’s great news for me, but not so great for the rest of the team!

How did my Contribution Change?

In this example, the amount of time I invested in Year 1 was higher than Years 2 and 3. Perhaps I ran out of savings in Year 1 and had to get a part-time job in Years 2 and 3 which would reduce my contribution — it happens!

When we take a look at my cash contribution, I was able to rustle up some cash to kick off our launch in Year 1, but after that, I wasn’t able to contribute more cash after that. I also had the initial contribution of the genius idea in Year 1, but I don’t get any value contribution in subsequent years for my genius in the first year.

My total commitment over 3 years was $120,000. If we were to project just Year 1 over 3 years, we would have assumed my relative commitment was $210,000 (Year 1 x 3 years).

Now we can see that without a mechanism to capture the actual value of the contribution over a period of time, we may disproportionately split our founder equity based on some wonky assumptions.

Using a Different Contribution Window

If for some reason we feel like 2 years is a better reflection of the contributions of our team – great! We can also extend it to 4 years to make it sync with our vesting windows (although not necessary). It’s also possible to do this in just one year, with the contribution windows being every 3 months. There are endless potential combinations, this is just a structure.

The duration of the contribution window isn’t the most important point here. It’s having a contribution window at all! Our primary focus is giving ourselves a check valve so that if we make some horrendous miscalculation about how members will contribute, we have a way to correct it. We also don’t disproportionately award long-term equity to short-term contributions.

“Hey wait — doesn’t “vesting” solve for the problem of non-contributors later?”

In an earlier section, we talked about stock vesting over a period of 4 years to allow equity to be returned if someone doesn’t stick around to make their full commitment. That’s all well and good, but that doesn’t account for how much stock they earn in that time.

The 3-Year contribution window determines the value of each member’s commitment. Vesting is simply a mechanism to return whatever they haven’t earned, no matter what the value

How we make adjustments Later

Up until this point, we’ve found a formula to fairly value our contributions. We’ve also put a 3-year window (or whatever time window we chose) in place so that we can adjust those contributions over time. Now we have to figure out how we’re actually going to make those adjustments over those 3 years.

The following years (and adjustments) work fairly similarly to the first year with one exception — the following years may see our equity swing quite a bit one way or another, and that tends to freak people out. Technically, we should all support the contribution we set out to make and everyone gets what’s expected, but we’ve already established the fact that this almost certainly won’t happen.

We’re going to need to make some adjustments over time, but we’ll want to make sure we have some expectations for how to make them fairly and what to do in case we want to prevent a massive swing in equity.

Review Founder Equity Splits Yearly

Each year we will sit down and review each member’s contribution relative to the other founding members of the company. During each review we will compare the intended contribution of each member with the actual contribution and make adjustments, recognizing that in some years the adjustments may create a bigger swing in favor of one member.

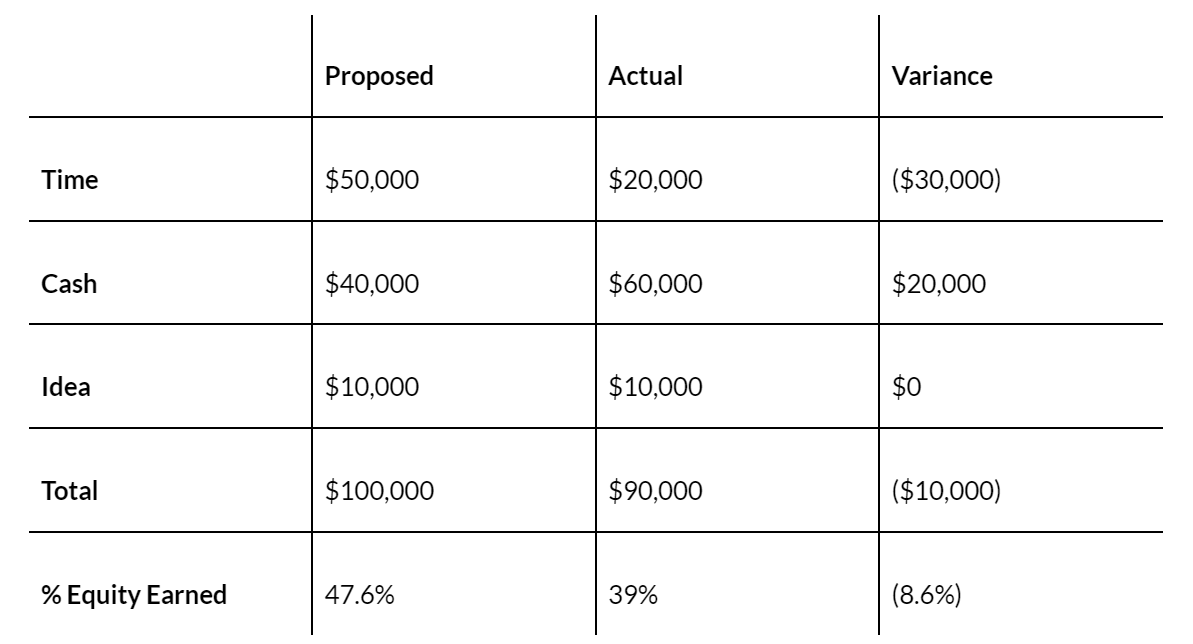

Our review of my contributions after Year 1 might look like this:

As you can see, my contribution isn’t that much different — but it’s different. If we weren’t reviewing this closely, I would have earned almost 9 more points in the company that I didn’t actually contribute. This compounds with each year that goes by, so those little differences can create large swings.

To be fair, it’s not always easy to track and calculate contributions like time or relationships, so the review may require some honesty and accommodation if there is a real issue between proposed contributions and tracked ones.

The Founder Stock Pool (Optional)

In other lessons, we've discussed the creation of an employee “Stock Option Pool” that would be set aside to award future employees based on the ongoing contributions that they make to the company as it grows. The Founder Stock Pool can work in the same way, only it can be used to mitigate how much our contributions affect our equity stake over time.

We’d use a Founder Stock Pool if we were concerned that our individual equity stakes may be too much at risk in the future. We may recognize that there could be swings in the future but may want to lock in a “minimum guaranteed stake” along the way.

Here’s a super simple example:

We each own 50% of the company. We agree to reduce our stakes to 40% each and contribute a total of 20% (10% from each of us) into the Founder Stock Pool. Based on our future contributions beyond Year 1, we will award the additional 20% dynamically over time based on actual contributions.

Our Individual Downside is Limited

In this system, we each get a minimum committed amount of stock (the 40%) but we also have an incentive to earn the rest of our contribution as we promised. If we don’t contribute what we intended, we don’t feel bad about the outcome because the system will automatically reward those that contributed more.

Splitting Future Years

In this case, when we review our contributions in Year 2 and beyond, we are only talking about making adjustments to the awards in the pool — nowhere else. If you put in 90% of the contribution in Year 2 then you would earn 90% of the pool (which is 20%). Each of us would always still have our base 40% relative to each other.

We would adjust the pool amount again in Year 3. Each adjustment is essentially a “temporary” adjustment until we reach our “Cutoff Year” in Year 3 which we’re about to explain.

The Founder Stock Pool is Optional

Note that we don’t have to have a stock pool. We can absolutely let our stock contributions change each year relative to the total contribution. There’s nothing wrong with that. The Stock Pool was mainly intended to limit the swings in our equity awards over time.

The Cutoff Year

In our examples, we’ve been using a 3-Year window as the target for valuing everyone’s contributions. Again, we can use 2 years, 4 years, or 12 months — depending on what feels right. That said, our determination on how many years does matter. If we agree a 3-Year window is the right move, then at the end of Year 3 – that’s our “Cutoff Year.”

After that point whatever we’ve earned gets locked in. That doesn’t mean it automatically vests, or that there are no possible provisions to lose that equity, which would be driven by things like our Operating Agreement in cases of a Termination for Cause or similar issue. That simply means we’re done calculating our founding member shares dynamically.

Are Short Terms Better?

There's no hard and fast rule here, but if it seems like the founding team is uneasy about doing anything other than an equal split, at the very least they can often agree on having some sort of short-term window just to confirm commitments beyond Year 1 or Year 2.

That could take the form of Founder vesting which simply means that each co-founder earns their stock over a period of time (let's say 2 years) so that if they leave in Year 1, they only get a portion of their stock.

Where to Begin

The best way to kick off this discussion is to ensure that the co-founders all agree that there is a risk of having a disproportionate share of founder equity based on near-term versus long-term contributions.

The equity split for founding teams is rarely a comfortable discussion, and because of that many startups and founders forgo the conversation altogether. They go back to the "equal share" concept not because they are contributing equally, but because they want to avoid the conversation, to begin with.

We've advised hundreds of thousands of startups on this issue and constantly battle against the default position of "equal splits." We get it! It sounds "fair" but invariably one party (or a few) will always wind up with the short end of the stick. Every now and again it works, but that's more a matter of luck than planning.

Sure, the conversation around what's equal is easy, but it leaves you open to all sorts of problems in the future. Instead, keep focused on what is equitable and you'll find yourself exponentially less likely to be dealing with equity split arguments or outright disasters later.

Founder Equity Matters

Upon framing this discussion with a co-founder remember that this is the most expensive decision you will ever make. If you think the equity split with venture capitalists is painful, consider the fact that this is likely a fraction of what they will take, and in their case, they are going to be handing you millions of dollars!

This is also wildly different than the traditional path small businesses take where they may have a few family members attached to it. These are often relative strangers — or at least people we don't have a ton of business experience with — where we're suggesting equal splits make sense before we even know who our co-founder really is.

There are plenty of ways to make this work, and as we've said this is really about being hyper-aware of all of the potential drawbacks to avoiding the conversation altogether and being left with a founder equity situation that we can't unwind.

So sit back, fellow founders, take a moment to think about how important what you're about to build really is and dig in on a tough conversation now to avoid years of challenging conversations in the future. A small, focused, investment in time now will yield incredible dividends in years to come by avoiding some of the most common pitfalls that tear startups (and their teams) apart. You'll be very glad you invested the time.

Find this article helpful?

This is just a small sample! Register to unlock our in-depth courses, hundreds of video courses, and a library of playbooks and articles to grow your startup fast. Let us Let us show you!

Submission confirms agreement to our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.

No comments yet.

Start a Membership to join the discussion.

Already a member? Login